Think about the communication model in the distributed system. We have either message passing(fundamental) or shared memory(convenient, but more abstract). The goal is to mimic single-process memory interfece so that higher-level algorithms can use this shared memory as a black-box. A read returns the value of the most recent write. However, in distributed system, operations may overlap. In this note, we build shared memory in the message passing communication model.

Outline

Memory consistency model: specify desired behaviors of shared memory

Linearizability (atomic consistency)

Sequential consistency

Algorithms for DSM

- Total-order broadcast (atomic broadcast)

- ABD (Attiya, Bar-Noy, Dolev, 1995)

Memory Consistency Model

What kind of consistency do we need for this piece of shared memory?

Definition(Linearizability) Let $S$ be a sequence of operations and responses. $S$ satisfies linearizability if there exists a permutation $S’$ of $S$ such that:

- Each op is immediately followed by its response.

- Each read of $X$ returns the preceding write to $X$.

- If op1 ends before op2 starts in $S$, then op1 occurs before op2 in $S’$. (respect the real-time ordering of non-overlapping operations)

Linearizability is also called atomic consistency (ops cannot be further divided).

Definition(Sequential Consistency) Let $S$ be a sequence of operation $i$ and responses. $S$ satisfies sequential consistency if there exists a permutation $S’$ of $S$ such that:

- Each op is immediately followed by its response.

- Each read of $X$ returns the preceding write to $X$.

- If op1 ends before op2 starts in $S$ at the same process, then op1 occurs before op2 in $S’$.

Respect the real-time ordering of non-overlapping ops at the same process.

Algorithms for DSM

For algorithms in distributed shared memory(DSM), we always want to consider the async, fault-free/crash faults model. WHY?

The async algorithms are more realistic and practical, as we don’t have to make assumptions about network delays. If an algorithm works in asynchrony, then it also works in synchrony. Also, in DSM, Byzantine doesn’t make sense, because we often consider same machine with many processors. Can’t assume processors are malicious against each other.

Definition(State Machine Replication). State Machine Replication (SMR) is a way to keep multiple replicas in sync:

- Intuitively, agree on a sequence of values $v$.

- Values come from external entities called “clients”. Value is also called “commands” or “requests”.

- Every process (also called a replica) executes the commands one by one (“state machine”)

- Safety: Cannot have $\log_i [s] \neq \log_j [s]$

- Liveness: Every request eventually gets into log.

Connection to DSM:

A “shared memory” is itself just a state machine whose state is the memory contents and whose commands are read/write operations. So, if we can run SMR over the network, we can implement DSM by treating the memory as a replicated state machine and agreeing on the global sequence of read/write operations.

Definition(Total-order broadcast) A broadcast protocol where all correct processes in a system of multiple processes receive the same set of messages in the same order.

Also called atomic broadcast. Realizing this protocol requires randomization in acync + crash. For the following algorithms, let’s assume we have a black-box access to this TO-broadcast.

Algorithm. Linearizable Shared Memory

The idea to build DSM is to use total-order broadcast:

- Each process replicates the full memory (or the initial common state, can be 0).

- New op invoked: send a new request.

- Op finishes when request is committed.

Proof. (Linearizability)

We want to show that there exists a permutation $S'$ of $S$ that satisfies the three properties in the linearizability definition, where the $S$ is the real time ordering. We do this by performing a method to construct $S'$. The method is to let $S'$ be the commited order in the TO-broadcast. We can check the three requirements.

- Each op is immediately followed by its response.

This is automatically satisfied by the TO-broadcast: request is followed by a commit.

- Each read of $X$ returns the preceding write to $X$.

This is also guaranteed by the TO-broadcast.

- Respect the real-time ordering of non-overlapping operations.

Op1 ended = decided in TO-broadcast

Op2 starts = input to TO-broadcast only later (respects real-time ordering)

Op2 is after Op1 in TO-bcast and hence in $S'$.

$\square$

Food for thought: why do we broadcast READs?

Answer: what if the read happens before and after a write?

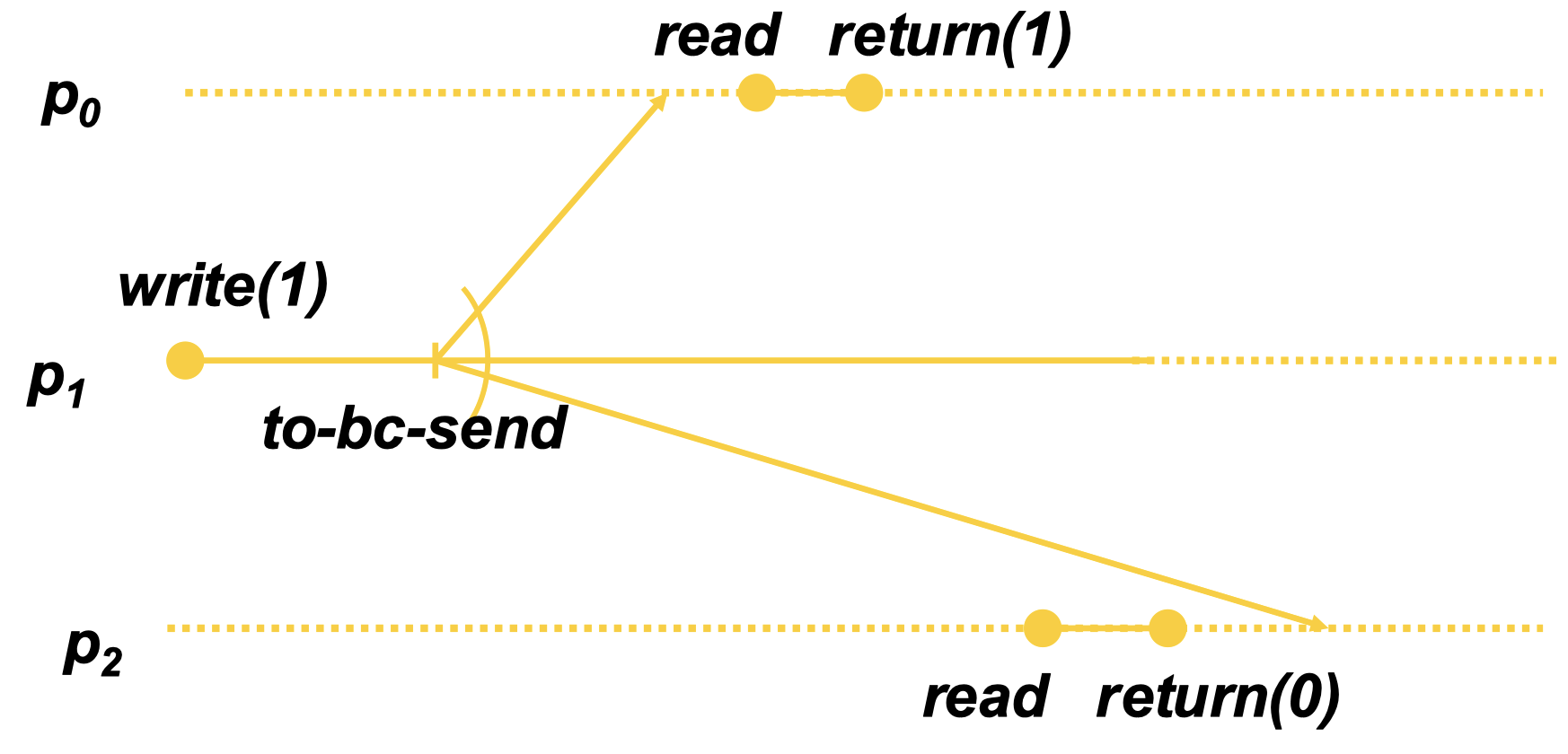

The example in the image reaches sequential consistency, but not linearizability. This is the result of not having the “read” broadcasted.

Algorithm. Sequentially Consistent Shared Memory

The idea is to use total-order broadcast, but only on writes.

- Each process replicates the full memory

- Write op invoked: send a new request

- Write op finishes when request is decided

- Read returns local replica right away

Proof. (Sequential Consistency)

Again, we need to construct a permutation $S'$ that satisfies the three properties in the Sequential Consistency definition. The way we construct $S'$ is to put writes in TO-broadcast order, and to put each read after latter of (1) preceding op at that process and (2) the write op it reads from.

- Each op is immediately followed by its response.

We force this to be true: each read or write request are followed by their commitments.

- Each read of $X$ returns the preceding write to $X$.

Need to prove this.

- If op1 ends before op2 starts in $S$ at the same process, then op1 occurs before op2 in $S’$.

By TO, the write ops are all satisfied as shown in the previous proof. For read ops, this is enforced by rule (1) of the construction of $S'$.

Subproof. (Each read of $X$ returns the preceding write to $X$.)

We need to show that another write $W'$ to $X$ doesn’t fall between this read $R$ and precedint write $W$. For contradiction, we assume that there is such a $W'$ in between $W$ and $R$:

$$ W(X, a) \quad\quad W'(X, b) \quad\quad R(X) = a $$If so, then this construction is not sequentially consistent. If $W'$ and $R$ are in the same process, $R$ would see $W'$ and returns $b$, which results in contradiction. If $W'$ and $R$ are from different processes, then by rule (1), the read $R$ will be put in the latter of some op $O$ at that process.

If $O$ is a write, then we must have $W'$ put before $O$ by the totol-order broadcast. $R$ sees $O$, so $R$ must also sees $W'$, which would return $b$ or whatever $O$ writes, contradiction.

If $O$ is a read, then we can recursively finds the first read op $O'$ in that chain. $O'$ is put there because $O'$ reads from $W'$. $O'$ sees $W'$, so $R$ also sees $W'$ and returns $b$, contradiction. $\blacksquare$

With all three properties checked, this algorithm is sequentially consistent. $\square$

ABD Algorithm

Previously, we assumed the total-ordered broadcast, which can be pretty expensive. Now, the ABD algorithm is a linearlizable shared memory algorithm is built in the message passing model. It is deterministic, asynchronous, and tolerates $f < n/2$ crashes.

Remark. It tolerates crash faults in asynchronous model. This doesn’t mean it breaks the FLP, but it means linearlizable SM is an easier problem than consensus.

Theorem(Linearlizability is composable)

If each memory cell is linearizable, the entire memory is also linearizable. In contrast, sequential consistency is NOT linearizable.

The proof of this theorem is very rigorous, but the intuition should be clear.

Now, we are back to the ABD algorithm. By the theorem, we only need to focus on one memory cell (also called a register). For now, we assume a single writer.

Algorithm. Attiya-Bar-Noy-Dolev algorithm (ABD)

For the register, we assume it is a tuple: $reg = (val, ts=0)$ initially, where the $ts$ is the timestamp.

Each process holds a register.

Upon write op:

$t \gets ts \gets ts + 1$.

Send $(\mathsf{update}, v, t)$ to all.

Upon receiving an $\mathsf{update}$ message (in other processes)

- $(val, ts) = (v, t)$ if $t > ts$.

- Send back $(\mathsf{ack}, t)$.

(The process who performed the op) wait until receiving majority $\mathsf{ack}$s.

We call step 2-4 $\mathsf{update}(v, t)$.

- Return after $\mathsf{update}(v, t)$.

Upon read op:

- Request local copy from all processes

- wait to collect majority copies

- $(val, ts) = (v_j, t_j)$ with largest $t_j$

- $\mathsf{update}(v, t)$

- return val to reader.

Remark. what’s wrong without $\mathsf{update}$ in read? Answer: otherwise, it is possible for two non-overlapping read to be inconsistent, while having a long write. The newest timestamp is not guaranteed to be a majority while the first read finishes.

Proof. Linearizability

Again, we need to construct $S'$ of the real-time ops and responses $S$ that satisfies the three properties in the Linerizability Consistency definition. We construct such $S'$ by sorting all completed operations by $ts$, if some operations have the same $ts$, we put:

The write first.

Then the read in the real-time ordering they completed (earlier read before later read).

Break any remaining ties arbitrarily.

By this construction, we prove the three properties:

- Each op immediately followed by its response in $S'$

We just attach the response right after the invocation; done by construction.

- Each read returns preceding write in $S'$:

A read op chooses the $(val, ts)$ with the largest $ts$. In $S'$, because we always propagate $(val, ts)$ to a majority, no operation with a larger timestamp that writes a different value can be missing by the read op. If there were, the read operation must see a bigger timestamp in the majority and choose that instead.

- Respect the real-time ordering of non-overlapping operations.

We need to show why the timestamp respects the real-time ordering. There are three cases: (a) $[R]$ before $[W]$, (b) $[W]$ before $[R]$, and (c) $[R_1]$ before $[R_2]$.

(a) $[R]$ before $[W]$ $\implies$ $R.ts < W.ts$ because $W$ increments $ts$ $\implies$ $R$ occurs before $W$ in $S'$.

(b) $[W]$ before $[R]$ $\implies$ $W.ts \leq R.ts$. By the time write completes, a majority receives and stores the new value and the new timestamp. When read op happens, at least one party relays this new value and new timestamp to the read op (by quorum intersection). Therefore, for non-overlapping $[W]$ before $[R]$, the chosen $R.ts$ must be $\geq$ the write timestamp $W.ts$.

(c) $[R_1]$ before $[R_2]$ $\implies$ $R_1.ts \leq R_2.ts$. This is for the same reason as in (b). The read operation relays the timestamp to others.

DSM Fault Tolerance

Claim. No algorithm for a linerizable 1-bit shared registers tolerates $f \geq n / 2$ crashes.

Proof. We partition the parties into two sets $S, T$, where $|S| \leq f$ and $|T| \leq f$. Assume the register $X$ has initial value 0. Consider the two executions:

- Execution 1:

- $S$: $[W(X, 1)]$

- $T$: some time after write finishes, $[R(X)]$

- Execution 2:

- $S$: nops

- $T$: $[R(X)]$

These two executions are indistinguishable to $S'$. Returning 1 breaks execution 2, returning 0 breaks execution 1. $\square$

Claim. There is no n-process message-passing algorithm that can implement two sequentially consistent 1-bit shared registers and tolerate f ≥ n/2 crashes.

The previous proof fails.

Proof. Consider the following three executions, where registers $X, Y$ are initialized to $0$. Suppose we partition the set of parties into two sets $S, T$, where $|S| \le f$ and $|T| \le f$.

- Execution 1:

- $S$: Write(X, 1), Read(Y)

- $T$: Write(Y, 1), Read(X)

- Execution 2:

- $S$: nops

- $T$: Write(Y, 1), Read(X)

- Execution 3:

- $S$: Write(X, 1), Read(Y)

- $T$: nops

In the first execution, a sequentially consistent algorithm must generate an $S'$ where either Read(X) returns 1 or Read(Y) returns 1, but it is impossible to have both reads output 0. However, because the size of the two sets are smaller than $f$, if the async network attacker delays the message between $S$ and $T$, parties in $S$ cannot distinguish execution 1 and 3, and parties in $T$ cannot distinguish executions 1 and 2.

At this point, if both partys’ read returns 0, it breaks execution 1. If Read(X) returns 1, then the execution 2 breaks. If Read(Y) returns 1, then execution 3 breaks. By this contradiction, we conclude that it is impossible to have a message-passing algorithm for solving this problem. $\square$