Items are NOT divisible now!

Goal: Fair and efficient allocation

Model

- $A$: set of $n$ agents

- $M$: set of $m$ indivisible goods

- Each agent $i$ has

- Valuation function: $V_i: 2^m \to R_+$ over subsets of items. This function is monotone, i.e. the more the happier.

- Allocation $X = (X_1, \ldots, X_n)$ is the allocation of goods to agents, where they form a partition of $M$.

Fairness

In the indivisible setting, we envy-free and proportional properties is hard to achieve in the divisible setting. We need new definitions.

Definition(EF1). Envry-free up to one item.

- An allocation $(X_1, \ldots, X_n)$ is EF1 if $\forall i, k \in N$, $\exists g \in X_k$ such that, $v_i(X_i) \geq v_i(X_k \setminus g)$.

- That is, agent $i$ may envy agent $k$, but the envy can be eliminated if we remove a single item from $k$’s bundle.

Definition(Prop1). The allocation $X$ is proportional up to one item if:

- $\forall i \in N, \; \exists g \in M \setminus X_i$ such that $v_i(X_i \cup \set{g}) \geq v_i(M) / n$.

- That is, each agent gets at least $1/n$ share of all items after adding one more item from outside.

Definition(EFX). Envy-free up to any item.

Efficient

Pareto-optimal: No other allocation is better for all

- An allocation $Y = (Y_1, \ldots, Y_n)$ Pareto dominates another allocation $X = (X_1, \ldots, X_n)$ if

- $v_i(Y_i) \geq v_i(X_i)$, for all buyers $i$ and

- $v_k(Y_k) > v_k(X_k)$ for some buyer $k$.

Fast Algorithms for EF1

Algorithm. Round Robin Algorithm(additive valuations)

- Fix an ordering of agents arbitrarily

- While there is an item unallocated

- $i :=$ the next agent in the round robin order

- Allocate $i$ her most valuable item among the unallocated ones.

Theorem

The final allocation of round robin algorithm is EF1 when the valuations are additive.

Proof. There are two observations:

- In each round, the first agent doesn’t envy anyone.

- In each round, for the $i$th agent in that round, if we remove the first $(i - 1)$ items allocated to the first $(i - 1)$ items allocated to the first $(i - 1)$ agents respectively, then the allocation is envy-free for agent $i$.

That is basically the proof :))) $\square$

Sometimes, we have more general valuations. They doesn’t have to be additive.

Definition(General Monotone Valuations). $v_i(S) \leq v_i(T), \forall S \subseteq T \subseteq M$, where $M$ is the set of all items.

Now, round robin doesn’t really help here. We need a better algorithm.

Idea. To do this, let’s first assume that some items have been allocated to the agents. Then, we draw direct arrows pointing from some agent $i$ to another agent $j$ that $i$ envies. OK, that’s fun. It is a direct graph! It could be some cycle, there will be some cycle elimination. If no cycle, then observe that no one is envying at the source!

Algorithm. Envy-Cycle Procedure (general valuations) [LMMS’04]

- $X \gets (\varnothing, \ldots, \varnothing)$

- $R \gets M$, the unallocated items

- While $R \neq \varnothing$

- If envy-graph has no source, then there must be cycles

- Keep removing cycles by exchanging bundles along a cycle, until there is a source. (Put the bundle on the ground, agents walk to the next bundle.)

- Pick a source, say $i$, and allocate one item $r$ from $R$ to $i$.

- Output $X$.

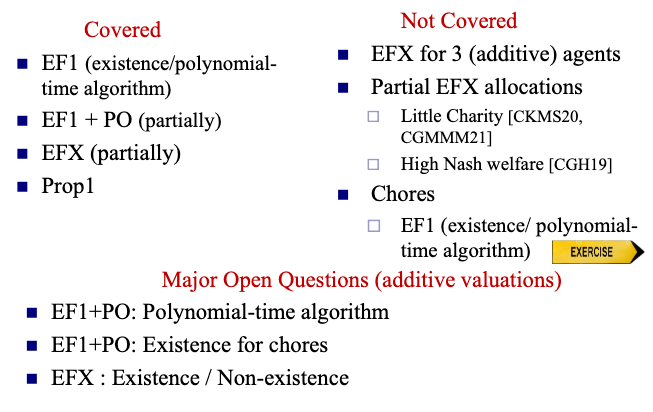

Now that we have a sense of the basic definitions, here is a summary of the current research topics:

Maxmin Share(MMS) [B11]

This is generalizing cut-and-choose

The Model

Suppose we allow agent $i$ to propose a partition of items into $n$ bundles with condition that $i$ will choose at the end. The idea is that $i$ would partition the items in a way that maximizes the value of her least preferred bundle.

$\Pi :=$ Set of all partitions of items into $n$ bundles.

Let $\mu_i :=$ maximum value of $i$’s least preferred bundle.

$\mu_i := \underset{(X_1, \ldots, X_n) \in \Pi}{\max}\; \underset{k \in [n]}{\min} v_i(X_k)$

MMS allocation: $X = (X_1, \ldots, X_n)$ is called MMS if $v_i(X_i) \geq \mu_i, \forall i$

- That is, we an allocation $X$ is MMS if each agent $i$ receives a bundle $X_i$ worth at least her maxmin share.

$\alpha$-MMS: $v_i(X_i) \geq \alpha \cdot \mu_i, \forall i$.

Additive valuations: $v_i(X_i) = \sum_{j \in X_i} v_{ij}$

Remark. Finding MMS value is NP-hard. The known fact now:

Polynomial-time Approximation Scheme(PTAS) for finding MMS value is possible [W97]

MMS allocation for $n = 2$ is possible

- A PTAS to find $(1 - \epsilon)$-MMS allocation for any $\epsilon > 0$

For $n \geq 3$ is impossible.

$\alpha$-MMS allocation for $\alpha \in[0,1]: v_i\left(A_i\right) \geq \alpha \cdot \mu_i$

- 2/3-MMS exists [PW14, AMNS17, BK17, KPW18, GMT18]

- 3/4-MMS exists [GHSSY18]

- $(3 / 4+O(1))$-MMS exists [AG23]

- 39/40-MMS does not exist [Feige et al. 2020]

Properties

- Normalized valuations:

- Scale free: $v_{ij} \gets c \cdot v_{ij}, \forall j \in M$

- $\sum_{j \in M} v_{ij} = n \implies \mu_i \leq 1$

- Ordered Instance: We can assume that agents’ order of preferences for items is same $v_{i1} \geq v_{i2} \geq \cdots v_{im}, \forall i \in N$.

Proof. of (2) in normalized valuations:

$$ \begin{align*} \mu_i = \min \set{v_i(X_1), \ldots, v_i(X_n)} &\leq \frac{\sum_{k = 1}^{n} v_i(X_k)}{n} && \text{min val $\leq$ average val}\\ &= \frac{v_i(M)}{n} = \frac{n}{n} = 1 \end{align*} $$$\square$

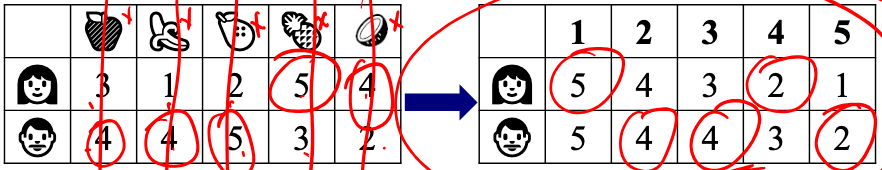

Proof. Ordered Instances

Say the leftside is a original instance, with each agent’s valuation. We simply sort their valuations, and don’t care about the mapping between the valuations and the name of the item. Now, for any allocation in the new instance, from left to right, it defines a picking sequence. In the example, we have ABBAB (Alice and Bob). Then, if we apply the same picking sequence in the original instance, and have the agent pick the most valuable item from unallocated items, the value of those bundles will only get better. That is, for any allocation in the ordered instance, there is a corresponding better(not worse) allocation in the original instance.

The observation is that when the $k$-th item is used, other agents’ value of that item in the original instance is only smaller than that in the new instance. Hence MMS only larger. $\square$

Approximating MMS

For the following, we just assume that all their valuations are sorted from largest to smallest.

Algorithm. Bag Filling Algorithm

Assuming $v_{ij} \leq \epsilon, \forall i, j$, and $v_i(M) = n, \forall i$.

Repeat until every agent is assigned a bag

- Start with an empty bag $B$

- Keep adding items to $B$ until some agent $i$ values it $\geq (1 - \epsilon)$

- Assign $B$ to $i$ and remove both

Claim. After round $k$, if $i$ remains then $v_i(\text{remaining goods}) \geq n - k$.

Proof. Since we have $v_{ij} \leq \epsilon$, for round $k$, when considering the last item we put inside the bag $B$ everytime, we know that the bag must have value $\leq 1$. After giving $B$ to the satisfied agent in round $k$, we have value $v_i(M \setminus B) \geq n - k$. $\square$

Theorem Every agent gets at least $(1-\epsilon)$.

By this theorem, since $\mu_i \leq 1$, getting $\geq (1 - \epsilon) \cdot 1 \geq (1 - \epsilon) \mu_i$ is already $(1-\epsilon)$-MMS. If $v_{ij} \leq 1/2$, then we already have a $1/2$-MMS algorithm. But what if $v_{ij} > 1/2$? The idea is to do some reduction.

Valid Reduction

A technique that helps us reduce fair division instance to a smaller instance. Can also see the definition in GMT19 paper.

If there exists $S \subseteq M$ and some $i^* \in N$ such that:

- $i^*$ gets $\alpha$-MMS value from $S$, i.e. $v_{i^*}(S) \geq \alpha \cdot \mu_{i^*}^n(M)$.

- Once we give $S$ to $i^*$, and remove both, the MMS value of the remaining agents does not decrease. $\mu_i^{n-1}(M \backslash S) \geq \mu_i^n(M), \forall i \neq i^*$.

Definition(Valid Reduction). If the above two properties are satisfied, then the removal of such $S$ induces a valid reduction.

Idea. If $S$ includes the item in the maxmin share of agent $i$, then agent $i$ actually gets better off (more chance to get more valuable item). Otherwise, it is not affecting the original maxmin share.

Claim. Suppose agent $i \neq i^*$ gets $X_i$ in an $\alpha$-MMS allocation of $M \backslash S$ to agents $N \backslash\set{i^*}$, then $\left(X_1, \ldots, X_{i^*-1}, S, X_{i^*+1}, \ldots, X_n\right)$ is an $\alpha$-MMS allocation in the original instance.

Algorithm. for 1/2-MMS allocation, using valid reduction.

- Normalize valutaions: $\sum_{j \in R} v_{ij} = n \implies \mu_i \leq 1$, where $R$ is the remaining items.

- Valid reductions.

- If $v_{i^*1} \geq 1/2$, then just give the item $1$ to agent $i^*$. (Assume valuation sorted.)

- Repeat 1 and 2 until we have $v_{ij} \leq 1/2$

- Bag filling algorithm

Claim. Step 2 is a valid reduction.

Proof. Suppose, for some agent $k$, this item $v_{i^*1}$ is in $k$’s maxmin share bundle. We know that $\mu_k \leq 1$, then the value of that item must also be less than $1$. After removing the item from $k$’s maxmin share bundle and giving it to agent $i^*$, the rest of the bundle can be placed in $k$’s other bundles, where the MMS value in this reduced instance won’t be decreased. $\square$

Algorithm. $2/3$-MMS allocation [GMT19]

- Normalize valuations

- Valid reductions:

- If $v_{i^*1} \geq 2/3$ then just assign item $1$ to agent $i^*$. (First valid reduction rule)

- Else if $v_{i^*n} + v_{i^*(n+1)} \geq 2/3$ then assign $\set{n, n + 1}$ to $i^*$. (CLEVER!!!)

- Repeat 1 and 2 untill no valid reductions.

- Generalized bag filling with $\epsilon = 1/3$.

- Initialize $n$ bags $\set{B_1, \ldots, B_n}$ with $B_k = \set{k}, \forall k$.

- Start assigning items starting from $(n + 1)$th to the first available bag, and give it to the first agent who shouts (who values it at least $2/3 = (1 - \epsilon)$ ).

Claim. The clever step is a valid reduction.

Proof. After the first valid reduction rule, we have $v_{ij} \leq 2/3$ for all agents $i$ and all remaining item $j$. After this, it suffices to consider the two cases for the “CLEVER” step:

Case 1: if $\set{n, n + 1} \subseteq X_k$, for some agent $k$. That is, if agent $k$’s maxmin share bundle includes both of these two items, we can treat it as a single item, and give it to agent $i^*$. The argument is the same as before (in the proof for valid reduction in $1/2$-MMS algorithm).

Case 2: if $n \in X_k, \; n + 1 \in X_l$, for some agents $k, l$, where $X_k, X_l$ are their maxmin share bundle. Since the item $n, n + 1$ are about to be given to agent $i^*$, for all $i \neq i^*$, we can change their MMS allocations by the following rule: find the bundle $X_d$ with items $j_1, j_2$, where $j_1 < j_2 \leq (n + 1)$, then swap $j_1$ with $n$, and swap $j_2$ with $n + 1$. For other items in $X_d$, assign it to other bundle. The bundle $X_d$ is then given to agent $i^*$. By this allocation, all agent’s MMS value will not decrease. $\square$

Claim. In the generalized bag filling algorithm, it agetn $i^*$ is the first to shout, then for any agent $i \neq i^*$, the bag is of value at most $1$.

Proof. First, by the valid reductions, we know that all items have value less than $2/3$. What’s more, after all the CLEVER valid reductions, it is impossible to have $v_{i^*n} + v_{i^*(n+1)} \geq 2/3$. Since the item $n$ is more valuable than item $n + 1$, we must have all item $n + 1, n + 2, \ldots$ being valued less than $1/3$. Combining with thes two facts, the generalized bag filling algorithm works exactly as before after having the first $n$ items initialized: the observation is that after last item added to the bag, the total value is of that bag is $\leq 1$ for all agents. $\square$

References

Ruta’s slides

[GMT19] Jugal Garg, Peter McGlaughlin, and Setareh Taki. “Approximating Maximin Share Allocations”. In: SOSA@SODA 2019. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.16788